Chapter One

Four young boys played marbles on the gritty asphalt surface of the alley, laughing and calling each other names that made even PI Hera Hunter, a former military sniper, blush as she walked past. Across the street two boys and a girl huddled on the bottom steps of a porch, staring at her so intently that Hera could see the suspicion in their eyes from across two lanes of traffic. At the intersection ahead, a teenage boy leaned against the street lamp, aimlessly watching the vehicles go by.

These were some of the children who called the streets of Centreville home. Abandoned, mistreated, neglected by those who should have cared for them, they sought safety and hope elsewhere. But on these streets they found neither.

The men and women on the sidewalks, heading with purpose toward diners, shops, and workplaces, rarely noticed them. Instead, the children blended into the brick facades of the buildings behind them. They were unseen and forgotten.

But Hera saw them. She saw them clearly.

She was ambling east along Van Buren Street. The rain had finally stopped, leaving pools in the depressions of the sidewalk and in the low spots of the narrow strips of grass that fronted the three-story tenement houses hovering over her. Gray clouds reflected off the puddles. The clouds were scattering as they moved north, allowing narrow rays of the morning sun to burst through.

Three doors up from her a fistfight between two girls broke out on the sidewalk. Six feet from them a dark green backpack lay on the wet grassy strip. It looked out of place.

She guessed the older girl’s age at fifteen. Tall and fit, she stood strong and confident, an angry expression on her face, giving Hera the impression she was a seasoned street fighter.

The smaller girl, a head shorter than the other, was younger by about a year. She kept her shoulders hunched, protecting her body. Her long brown hair had become entangled with her arms, which she held high to shield her head.

Denied a clear target, the taller girl began jabbing at her rival’s defense. The smaller girl absorbed the blows, but her arms began to sag. A few more punches and her head would be exposed.

Hera had little tolerance for an unfair fight. She gathered her chestnut hair in her hands, coiled it to form a single length, and pushed the long coil beneath the back of her coat. Her hair now protected from grasping hands, she pulled a ten-dollar bill out of the front pocket of her jeans and approached the altercation.

She seized the shorter girl by the collar of her coat and dangled the note in front of her opponent. “I’ll give you ten bucks to get lost,” she told the taller one. “Now,” she said in a sterner voice.

The girl grabbed the money. Then she picked up the backpack and took off down the street.

“Hey!” yelled the child in Hera’s grasp. “Hey!” she repeated as she squirmed to break free. “Let go of me!”

Hera held on to her collar firmly. She became conscious that she towered above the child. But at five feet nine, most kids seemed pint-sized to her.

She glanced over the frayed edges of the girl’s coat sleeves, the rips across both knees of her jeans, and the hole along the outside edge of one running shoe.

“Settle down, and I’ll let you go,” she said.

It took a while, but the girl did calm. Hera released her grip and leaned forward until they were face-to-face. The girl’s eyes were brown and widely set. One of her top front teeth was chipped.

The girl met Hera’s gaze with an unblinking stare that could only be called combative. But Hera saw the pain beneath the hostility. She knew the look well, because she, too, had once been a child of the streets.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“Calamity Jane,” the girl said with a smirk.

Hera knew that wasn’t the girl’s given name, but she didn’t press the matter. The street children often assumed colorful monikers to hide their true identity from the authorities. And each kid learned quickly that if you wanted to survive, you avoided questions by either lying or keeping your mouth shut. You learned not to trust strangers and their endless prying since you never knew who they really were or what they really wanted from you.

“Then I’ll just call you Calamity,” she said. “My name’s Hera.”

The girl shrugged. Her stomach rumbled.

“You hungry?” Hera asked.

Suspicion knitted the girl’s brows. “Maybe,” she said.

“Come on. I’ll get you something to eat.”

Calamity hesitated. “Where are we going?” she asked.

“Just over there.”

Hera pointed across the street to a storefront a couple doors farther east from where they now stood. Directly behind the window to the left of the shop’s front door, boxes of oranges, grapefruits, and other fruits sat on terraced shelves. The window on the other side of the door displayed tomatoes, cucumbers, potatoes, and onions, all arranged in neat mounds. Above the door a sign announced Bernie’s Market in big black letters.

“Have you ever been in Bernie’s before?” Hera asked.

The girl hesitated. “Yeah,” she said.

Hera suspected the girl was lying. She wondered how long Calamity had been on the streets since all recently arrived runaways soon heard about Bernie’s.

“Come on,” she said. “I bet he has a big pot of beef stew heating on the stove and a crusty loaf of bread sitting on the kitchen counter. It’s the best beef stew in town.” She stuffed her hands into her coat pockets and stared at the child, waiting for her to make up her mind.

“If I come with you, will you give me ten bucks, too?”

“Sure.”

“Okay, then.”

After letting a pickup truck in the near lane pass, they walked across the middle of the street and entered the small grocery store. The room was just big enough to accommodate the five rows of closely spaced shelving units that ran from front to back. Large round mirrors hung from the ceiling at all four corners, allowing the cashier at the front to watch the entire store, a must in this neighborhood of seedy flats, pawn shops, tattoo parlors, and a Laundromat.

Just inside the door, an elderly woman wearing a faded brown coat waited by the cash register. Behind the counter Tommy, a street kid Bernie had taken in two years ago, was bagging the woman’s purchases. He had a round face and light brown hair that flopped into his eyes whenever he moved his head.

Along the center aisle, Felix, another of Bernie’s young charges, was cramming cereal boxes onto the top shelf. At twelve years of age, he was three years younger than Tommy. He had a ready smile and always wore jeans that were a size too big for his chubby frame. As he reached for the shelf, his tee shirt rode up, revealing the waistband of his briefs.

“Hey, Felix,” Hera called to him.

The boy stopped what he was doing and turned his eyes toward the door. His face broke into a smile. “Hey, Hera,” he said. He waved to her.

“Good to see you, Hera,” Tommy called from behind the counter.

“Is Bernie around?” she asked.

“He’s in the back,” Tommy said.

Hera returned the elderly woman’s pleasant smile, then she and Calamity started down the center aisle. When they reached Felix, they stopped.

Hera pulled two baseball cards out of the pocket of her corduroy vest. “Look what I found,” she said to Felix.

He took the cards and looked them over. “Wow,” he said, grinning from ear to ear. “Dick Groat and Floyd Robinson! Where’d you find them?”

“At a sidewalk sale on Second Avenue. I wasn’t sure if you already had them so I thought I better pick them up.”

Felix was an avid baseball fan. He looked at the new additions to his card collection as if they were each worth a million bucks. “I don’t have them. Thanks, Hera.”

“My pleasure,” Hera said. Then she and Calamity continued on their way.

The door to the back office hung open, exposing a cramped area with too much furniture for its space. A gray metal table that served as a desk stood along the back wall. Its surface held a computer screen surrounded by a disarray of papers and envelopes and manila folders. A well-used armchair padded in red faux leather serviced the desk. In one corner of the room, a small square table offered a coffeemaker that had seen better days. Ceramic mugs, packages of sugar and Cremora, and a pile of swizzle sticks lay beside the machine. In another corner sat a wooden high-back chair that had lost its seat cushion. Hera had often wondered how Bernie Winkler managed to squeeze his ample waistline through the room’s narrow empty spaces.

Bernie was sitting in the armchair, sipping a mug of coffee and staring at his computer screen. Since his wife died seven years ago, he’d dedicated what little he owned to helping the homeless kids who hung around the nearby stoops and alleyways. He kept a pot of hearty stew on the stove and loaves of raisin bread on the counter in the kitchen of his upstairs flat. A spare room of the apartment had been converted into a bedroom, which he’d furnished with two bunk beds and two small chests of drawers. Tommy and Felix occupied the lower berths. The upper berths waited for the knock on the downstairs door by any boy in need of a safe place to rest for the night.

Bernie glanced up when Hera and Calamity entered. Then he stood. “Hera,” he said. “It’s good of you to stop by.”

“Hi, Bernie,” she said.

His height matched her own. Graying black hair along the sides and back of his head set off a bald pate that gleamed in the fluorescent light of the ceiling fixture. He wore black pants that pinched his waistline and a white shirt with long sleeves rolled up to his elbows. She’d never seen him in a tie.

His eyes moved to Calamity’s. “And who is this young lady?” he said. He offered the girl his hand.

She ignored it. She looked up at Hera as if confused by the friendly gesture.

“Her name’s Calamity. I told her you made the best beef stew in town,” Hera said.

“Well, then, we’ll have to prove it. Would you like to try some?” Bernie said.

Calamity nodded.

“Felix,” Bernie called out, so suddenly that the girl jumped.

“Yeah?” Felix said when he appeared in the doorway.

“Please take this young lady upstairs and give her a bowl of stew and a glass of milk. And I think there’s some chocolate chip cookies in the cupboard.”

“Sure,” Felix said. He turned to Calamity. “Come on,” he said, and he preceded her out of the room.

“How about a cup of coffee?” Bernie said.

“Love one,” Hera responded.

“Grab a chair.”

While he busied himself at the coffee machine, Hera removed an envelope from her coat pocket and placed it on the desk. Then she grabbed the wooden chair from against the corner and carried it nearer to the armchair. She sat down and watched him put Cremora and sugar in her cup. She preferred it black, but he never remembered that and she had ceased reminding him long ago.

While he stirred the coffee with a swizzle stick, she looked over the large familiar travel posters that hung on the walls. Her eyes lingered on the Ducal Palace of Venice. Then her gaze moved on to the Baths of Diocletian in Rome and finally rested on the Il Duomo in Florence.

Bernie and his wife had spent two years planning their dream vacation: a three-week tour of Italy. They had saved for years in order to afford it. They even attended courses to gain a basic understanding of the language. On the evening that their plane was to whisk them off to Europe, Bernie’s car slid on a wet and slippery road and wrapped itself around a telephone pole. He walked away from the car unharmed. His wife died instantly.

Hera thought he kept the posters on the wall as a reminder of the woman he loved and the dream they had shared.

“Here we go,” Bernie said as he set the mug on the desk.

“Thanks,” she said.

He lowered himself slowly into the armchair, as if all his joints ached. Then he picked up the white envelope and placed it in one of the manila folders. “Thank you,” he said.

Hera nodded. She didn’t need the words of gratitude; she just wanted to help. Once a month she dropped by with an envelope full of cash to help Bernie with the costs of feeding the hungry children, who knew they could always get a meal at Bernie’s Market.

She took a sip of the coffee and did her best not to grimace at the sweet taste. “So, how’s business?” she asked.

She listened quietly while he complained about the construction noise and the heavy truck traffic surrounding Good Samaritan Hospital, which was located a block up the street. Two new floors were being added to the children’s wing. She had little to offer on these subjects, but she was a good listener. He’d just turned his attention to a recent article about police corruption in the Centreville Times, the city’s leading newspaper, when loud voices erupted in the flat above them.

They both looked up as if they might see the disturbance through the ceiling. Footsteps thundered down the stairs that led to the flat. The street door that gave access to the stairwell slammed shut.

“What’s going on?” Bernie said.

Hera shook her head. She didn’t have a clue.

Moments later Felix appeared at the office door, his face wan and his lips pressed tightly together. The boy was trying mightily to hold back his tears.

“What’s the matter?” Hera asked him.

Tears spilled from his eyes and flowed down his chubby cheeks. “Calamity stole my new baseball cards,” he blurted out.

Hera frowned. Then she rose from her chair. “I’ll go talk to her,” she said.

“You can’t,” he sobbed. “She’s gone. She ran away.”

Chapter Two

When Hera stepped out of Bernie’s Market, she bumped into a husky young man with a carefully trimmed beard. He was rushing down the sidewalk. “Excuse me,” she said.

He ignored her apology and continued west.

Her gaze followed his progress, and she saw that others, too, were hurrying toward the intersection west of the market. Now curious, she decided to join them.

The crowd stood in silence as she neared. Tension filled the air. She pushed through the men and women until she reached the front and saw what had drawn their attention.

Entangled in a yew bush next to the concrete porch of a tenement house was the tall teenager she’d seen earlier fighting with Calamity. The girl lay upon her back, her legs twisted and her head resting awkwardly against one shoulder. Clearly, her neck was broken.

Hera looked up, suspecting that the girl had plummeted from the tenement’s roof. Red brick, darkened with age, covered the building’s façade. Three evenly spaced windows marked each of its three levels. Their placement indicated that the inside stairwell hugged the west wall. A hand-drawn sign taped to one of the windows on the ground floor held the words ‘Fortune Teller’. Below the words was a telephone number.

She retrieved her cell phone from a coat pocket and dialed the police. She reported the situation in as much detail as she knew, which was little. When the officer asked her to identify herself, she hung up.

“What happened?” a man in the crowd asked.

“She fell from the roof,” a woman answered.

“What was she doing on the roof?”

“I don’t know. But something needs to be done about these homeless children. They’re always hanging around. They should be gathered up and taken back to wherever they belong.”

Hera didn’t like the anger in the woman’s voice. “Many of these children have no homes to return to,” she said. “Perhaps you have room at your place to take one of them in.”

The woman gave Hera a disapproving look. Then she turned and joined those who were already drifting away from the scene, their curiosities satisfied.

She noticed her friend Rabbit among those leaving. Now fifteen years old he’d lived on the streets for as long as she could remember. Everyone knew and liked him. Even the shopkeepers and beat cops, who often chased the street children away, were counted among his friends.

Hera considered calling out to him, but she wanted to linger. Someone cared about this girl. She had a mother and a father, parents who loved her very much, even if they didn’t love her very well. They would not want their daughter lying alone in a strange place, ignored and forgotten. She decided to stay until the police arrived.

She wasn’t the only one to remain. As the crowd dwindled, Hera fixed her eyes on the girl in the shabby coat and ripped jeans. Hera was no stranger to fear. She saw it now in Calamity’s eyes. The girl was staring at something farther down the avenue.

Hera turned to look and saw a man dressed in a tan overcoat walking briskly away from them. She noted the confident step to his walk and the determined set of his broad shoulders. His long brown hair swung loose across his back.

At first she thought the man was following Rabbit, who hurried before him with his typical limping stride, the result of a broken leg that didn’t heal properly. Then she saw the Cadillac XTS with darkened windows heading north toward them. The vehicle stopped, and the man opened the right front door and slid into the passenger seat.

The Cadillac continued north. As the vehicle passed the intersection, Hera strained to read its license plate. But the car behind it followed closely and blocked her view.

The Cadillac sped up, gaining distance from the vehicle behind it. Hera squinted to read its plate, but the vehicle was now too far away. So she turned her attention to Calamity.

The girl didn’t notice as Hera approached.

“Are you all right?” Hera asked.

Calamity didn’t answer. She stared into the distance as if oblivious to her surroundings. She appeared to be in distress.

Hera grabbed her by the shoulders and shook her gently. “Calamity,” Hera said to get her attention.

The words awakened the child. “Let go of me,” Calamity said.

Hera removed her hands. “Who was that man?” she asked.

“What man?”

“The man you were staring at. The one in the tan overcoat. Who is he?”

Calamity shrugged. “I don’t know anyone in a tan overcoat.”

“Then why are you afraid of him?”

“I’m not afraid of anyone.”

“Looked like it to me.”

“Yeah, well, what do you know?”

Another crowd was forming around them. Many in the group were young boys. They pushed and shoved each other to get a better view.

Hera gazed at the girl sprawled within the yew. “Who is she?”

“Another street girl,” Calamity said.

“She must have a name.”

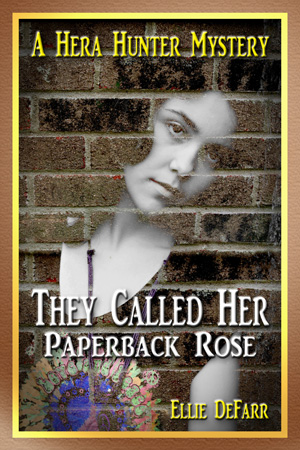

“They called her Paperback Rose.”

“Did you know her well?”

Calamity shook her head.

“You weren’t friends?”

“I told you, I barely knew her.”

“What were the two of you fighting about earlier this morning?”

“It was just a misunderstanding.”

“About what?”

“A boy, okay. It wasn’t anything.”

Hera sighed, figuring she’d get more information out of the yew bush embracing the dead girl than from Calamity. She listened to the conversations around her.

“Look, that’s Paperback Rose,” a young boy said.

“She must have fallen out a window,” another said.

“No, stupid, she fell off the roof,” came from a third.

“How do you know where she fell from?” the previous boy said.

“Are you blind? The windows are all closed.”

“Why is she called Paperback Rose?” Hera asked.

Calamity shrugged. She seemed to favor the gesture. “She said her name was Rose. And she always had her face in a book.”

A woman of middle age emerged from the front door of the tenement house. She wore a shapeless green housedress and a red scarf over her hair. “What’s going on?” she said to the crowd. Then she saw Paperback Rose and slapped her hand over her mouth to muffle her scream.

Hera looked toward the top of the building again. “I wonder what she was doing up there,” she said.

“I wouldn’t know,” Calamity said.

Hera continued staring at the roof. Something had drawn her attention. “I don’t understand how she could accidentally fall,” she said. “All these tenements have flat roofs with tall parapets that would have protected her.”

“She didn’t fall,” Calamity said.

“What do you mean?”

“She didn’t fall. Someone pushed her over the edge.”

Hera studied Calamity’s face, suspecting the girl was making up a story. But the expression in the girl’s eyes suggested she believed her words.

“Did you see who pushed her?” Hera said.

“No.”

“Were you up on the roof with her?”

“No.”

“Then how do you know she was pushed?”

Calamity shrugged.

Hera took a slow, deep breath to control her rising anger. “Why would someone push her?” she asked.

“How would I know?”

Hera glanced toward the sounds of sirens drawing near. They came from about a block away. The boys started to scatter. She grabbed Calamity’s arm before the girl could join them.

“Before you go,” Hera said, “I want the baseball cards returned. Give them to me.”

“What baseball cards?” Calamity said.

“Just give them to me.”

Calamity withdrew the pictures of Dick Groat and Floyd Robinson from her coat pocket. She slapped them onto Hera’s outstretched palm. “I didn’t want them anyway,” she said. Then she gave Hera a belligerent look. “And you promised me ten dollars.”

“Do you expect me to give you money after you stole from my friends?” Hera said. She stuffed the cards back into her vest pocket.

“Yeah, well, you shouldn’t break your word.”

Hera retrieved another ten-dollar bill from the pocket of her jeans. “You’re right,” she said, “I shouldn’t.”

She handed Calamity the note then frowned while the girl threw her arms around her and hugged her tight.

She didn’t like children. She didn’t like their lies and their mess and their noise. She didn’t know how to handle them, and she lacked the patience to learn.

Calamity stepped away from her. “Thanks for the ten bucks,” she said.

“Yeah, sure,” Hera said.

She watched while the girl hightailed it out of there. The girl was lying about something. But before she could give it much thought, she noticed that she wasn’t the only one watching Calamity leave.

A teenage boy was staring after the girl. He had blond hair and a sparse mustache and stood with his lips pressed together. A large stain marked the front of his pea coat. Its sleeves weren’t long enough to reach his wrists.

Street kids were good at hiding their feelings. Appearing weak had a way of inviting trouble. Hera couldn’t read the expression on the boy’s face, but it didn’t look friendly.

She stepped toward him. “Excuse me,” she said.

His head turned. His eyes held hers for just a moment. Then he took off running in the opposite direction as Calamity.

Hera sighed as she watched him quickly disappear. She didn’t waste her time chasing him. Like all street kids he knew how to maneuver the roads and alleyways to evade a pursuer.

The morning was not going well, she thought.

She headed back toward Bernie’s Market, intending to return the baseball cards to Felix. She reached into her vest pocket to retrieve them, but the cards were now gone.

She stopped abruptly and swore at herself. She should have known better. Calamity had retaken them during her hug, and Hera hadn’t felt the girl’s grubby little hands slipping under her coat. Calamity was a skilled pickpocket. She would have to remember that.

Chapter Three

Two days later Hera sat at her desk in the office of her firm, Hunter Investigations. It was on the second floor of Brandt Plaza, one of the many office complexes along Central Avenue, the city’s main street.

She was cataloging photographs, mail, and notes related to a missing person’s case that she and her colleague, Toby Isles, had just successfully completed. Toby usually handled the paperwork since it required a level of patience Hera rarely felt like mustering. But she had a few minutes before her 10 a.m. appointment arrived, and she wanted to put the time to good use.

Just as she finished titling and sealing the last of three large white envelopes, Lucky, her small black and tan dog, began a low growl, warning her that someone was approaching in the corridor outside. He’d been sleeping within the desk’s kneehole, his head resting upon her foot.

Hera stopped what she was doing and listened to the staccato tapping of high-heeled shoes that were drawing near. Moments later she heard a soft knock on the wooden frame that surrounded the door’s frosted glass insert.

“Ruff, ruff,” Lucky cried. He jumped to his feet and stiffened with caution. As the door slowly opened, he uttered another low growl, scooted behind Hera’s chair, and sank low onto the floor, safe now from any danger.

A round face encircled by loose brown curls appeared in the opening between the door and its frame. “May I come in?” the woman asked.

Hera abandoned her chair to greet her guest. “Of course,” she said, making her way across the room. “You must be Helen Stimson.”

The woman nodded as she stepped lightly into the office.

“I’m Hera Hunter.”

“Yes, we talked on the phone yesterday.”

Helen Stimson was of average height and trimly built. She had rouged her cheeks, covered her lips with a pink gloss, and thickened her lashes with mascara. But none of it softened the pain in her deep blue eyes.

She’d refused to explain what business drove her to seek the assistance of a private investigator when she made the appointment. Hera had sensed that the woman felt uncomfortable talking over the phone so she didn’t press the matter.

“Let me take your coat,” she said.

“Thank you.”

The woman slipped her dark blue coat off her shoulders. Beneath it she wore a pink wool suit that flattered her figure. Its cut and fabric suggested a cost that was neither cheap nor terribly dear.

A practical shopper, Hera thought. She took the woman’s wrap and laid it over one of the padded guest chairs that lined the side wall. “Why don’t we sit at my desk in case I need to jot down some notes? Would you like something to drink, Mrs. Stimson?”

“No, I just had some coffee. But thank you. And, please, call me Helen.”

Hera waited for Helen to make herself comfortable in the armchair beside her desk. Then she resumed her seat behind it. “Now, how may I help you?” she said.

“I’m Rita Stimson’s mother,” Helen said, almost choking on the words. Tears wetted her eyes. They started to flow.

The name meant nothing to Hera. She pulled a box of tissues from a drawer of the desk and dropped the box in front of the woman. Then she waited while Helen composed herself.

During the six years she’d been a PI, she’d never figured out how to handle a crying client. That she couldn’t empathize with the client caused her some discomfort, for she thought that was the least she should expect of herself in her business.

But how could she feel their grief when she felt little of her own? She hadn’t once shed a tear since she was eight years old and watched her father murder her mother. He then abandoned her, leaving her to the cruelties of living on the streets and the abuses of the foster care system.

Hera felt no pity for herself. The fear and loneliness she lived with as a child had not broken her. Instead, she had become strong and self-reliant, and perhaps a bit withdrawn.

“I’m sorry,” Helen said as she snorted into a tissue. “My beautiful daughter didn’t commit suicide, as the police are saying. She didn’t jump to her death from the roof of some tenement house. Something happened on that roof, and I’d like you to find out what.”

Hera suddenly realized that before her sat the mother of the teenage girl who’d spent her final moments entangled in a yew bush not far from Bernie’s Market. Hera kept quiet about her presence at the scene of the girl’s death. She didn’t think it was the right moment to insert herself into this family’s tragedy. She also held back that Calamity Jane believed the girl had been pushed over the roof’s edge. Nor did she share the fact that among the street children her daughter was called Paperback Rose. None of it seemed appropriate at the moment.

She hadn’t followed Rose’s story in the Centreville Times since the police were handling the case. She preferred to avoid the trouble that would ensue if she intruded into their territory. Unless, of course, someone hired her to look into the matter.

“Have you talked to the police?” she asked.

“Yes, my husband and I have,” Helen said. “They claim there’s no indication of foul play and that she either fell or jumped. They don’t think she fell since a four-foot-high wall runs along the edge of the roof. But she wouldn’t have jumped. She just wouldn’t have.” She started to sob.

Hera waited while the woman dabbed her eyes with a tissue. She wondered if the office had another box of them; they were disappearing fast.

“I understand your daughter was a runaway,” she said.

Helen nodded as she wiped her nose.

“She lived on the streets?”

Helen nodded again.

“When did she leave home?”

“About two months ago,” Helen said. She expressed a deep sigh then settled against the back of her chair. “Rita told us she was going to visit her best friend. She didn’t come home that night. My husband and I were frantic and called the police. They said their policy was to wait forty-eight hours before looking for a missing fifteen-year-old. Three days later Rita called and told me that she would not be returning home and that we were not to worry about her. I thought she sounded well and happy. We reported the call to the police, and they ended their search for her.”

Hera had heard the story many times before. Typically, the child sought freedom from a physically or sexually abusive home. Or the kid could no longer stand the strict and relentless discipline of their home environment.

“Did your daughter explain why she left?” she asked.

“No, but she didn’t have to,” Helen said. “She and her father fought relentlessly. He’s very strict with her. And Ned, my husband, is demanding and critical. She’d threatened to run away before, but we never thought she was serious about it.”

“What happened that made her finally follow through on her threat?”

For a moment the question seemed to confuse Helen. Then she said, “Nothing that I know of.”

“Did your husband ever hit your daughter?”

“Oh no, he never hit her. When she disobeyed him, he punished her by locking her in her bedroom. But he never hit her.”

“I have to ask this, so please don’t get upset,” Hera said. “Is it possible your daughter was sexually abused?”

“No,” Helen said firmly. “Ned wouldn’t.” She withdrew into silence, thinking. A dark thought, judging from the look in her eyes. “He just wouldn’t.”

But Hera wasn’t so sure. She thought, perhaps, Helen wasn’t either. “What kind of work does your husband do?”

“He’s a project manager at Wilkins Tech.”

Hera knew of the company. They worked exclusively for the Department of Defense. “What does he do there?”

“He supervises the engineering designs for the next generation of guided missiles.”

Hera couldn’t see any connection between the Defense Department and this woman’s troubles so she said, “If you don’t think your daughter jumped off the roof of the tenement, what do you think happened to her?”

Helen frowned. “I don’t know. I suppose she just fell off. But I’d like to know what she was doing up there. And whether it’s possible she slipped and fell. She couldn’t have jumped. She was a happy girl.”

Not too happy, Hera thought, otherwise the child would not have left the safety of her home. “I noticed your husband didn’t come with you,” she said.

“He’s in the hospital, but he’s being released this afternoon. He suffered a mild heart attack when we learned that our daughter had killed herself. He blames himself for being so hard on her.” Helen took a deep breath as if she found it difficult to continue. “But I don’t believe she jumped to her death.”

“Just a few final questions,” Hera said. “Does she have any brothers or sisters?”

“A younger brother, Patrick. He’ll be ten years old next month. He and Rita were very close.” She started to sob again.

“Is there anyone your daughter was close to whom she might have confided in? A friend? Perhaps a relative?”

“Yes, my sister, Agatha Kearny. She lives on Turing Street, not far from us. But she hasn’t had any contact with Rita since she ran away.”

“What about a close friend? Someone her own age?”

“She sometimes hung out with girls in her class at school. But she had only one close friend, Kendra Hutson. She lives down the street from us. But Kendra said she saw my daughter only once after she left home. Rita asked her for money. Kendra gave her all the money she had with her, which wasn’t much. A little over twenty dollars, I think.” Tears spilled onto her cheeks.

Hera glanced around the office for another box of tissues. She didn’t see any. She did notice that Lucky had moved to his favorite place in front of the radiator. She lowered her eyes to the papers on her desk and let Helen cry in peace.

When the office once again grew calm, she said, “I’ll be glad to look into your daughter’s death.”

Helen’s face brightened at the words. She let out a deep sigh of relief. Hera thought that by taking the case she might have uttered the first good news the woman had heard since her daughter left home.

newline

New Characters

Paperback Rose:

a street urchin; always has her face in a book; loves Daphne Du Maurier novels

Calamity Jane:

another child who lives on the streets; she and Rose watch each other’s back; she knows something that’s got her very frightened

Rabbit:

he’s been on the streets for as long as Hera can remember; liked and trusted by all, even the police and shopkeepers

Clement Isles:

a state senator; Toby’s older brother; he’s up for reelection, and according to the polls he’s about to lose his job

Woody Talford:

a private investigator; he’s smart, observant, and thorough; he’s also a pain in Hera’s butt

newline

Main Characters

Hera Hunter:

female sleuth; former military sniper; vigilante; strong and dangerous

Lucky:

small black and tan dog; Hera’s faithful sidekick

Toby Isles:

Hera’s man Friday; skilled computer hacker; hostile to conventional mores

Billy Fenn:

Hera’s foster sister; madam of a high-class brothel; educated and well read

Gwendolyn Oates:

Hera’s drinking buddy; cat burglar; flirtatious and fun loving

Letitia Leeping:

police detective; former military sniper; tough but honest

Wim Carter:

Hera’s oldest friend; lead investigative journalist for the Centreville Times